The Viennese whirl, Franz West, was as versatile as he was eccentric. His art brings together papier-mâché, old bottles, furniture, the human body, and a dozen other random things. Seven years after his death, the Tate Modern reintroduces West in all his range.

Divento went to an exhibition on Renaissance nude painting before turning up at the Tate, and they couldn’t be more different. The Renaissance Nude at the Royal Academy is an old-school display: focused, historical, and detailed. Franz West was never going to do well with the RA treatment. His work is extraordinarily varied. The Tate was probably right to arrange West’s pieces in stages of his life. The timeline of a human biography might be the only one loose and flexible enough to accommodate the work of someone like West, who experiments in every direction. Sarah Lucas, one of his friends, has designed the walls and pedestals that bring order to this collection.

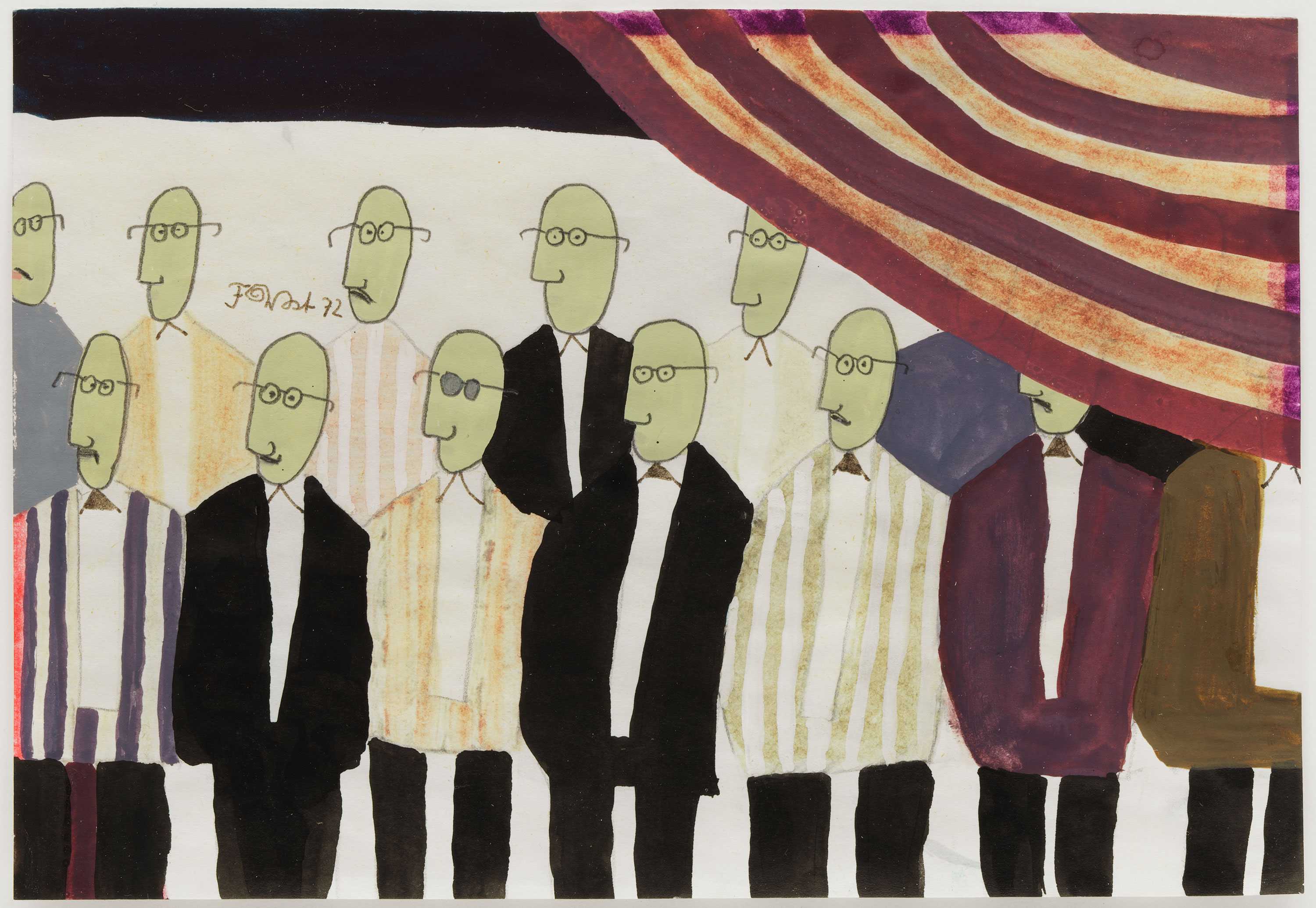

As we learn from the first room, West was interested in subverting the mass media, sexuality, interacting with visitors, and childhood. But this list isn’t exhaustive. Faces are important to West, as well as modern life and, weirdly, anything shaped like a worm. Sex Trivial (1972) is a casual, almost flippant portrayal of the female body, which parodies pornography. Like Lowry, the young West has a particular way of drawing people: pointy heads and narrow suits. But he quickly moves away from it. The faces of the 1970s Untitleds have ornate moustaches and thick eyebrows, while textured, flush faces come in the Frohsinn (1974). West thought that Sigmund Freud saw sex where there wasn’t any, and West is always elbowing Freud in the ribs for this. Sex in West’s early work is over-exaggerated, and as silly as it is ugly.

Already in Room 2, we’re faced with seven distinct artistic projects. Mickey-takes are important here: of Marxism, intellectualism, and again porn. But the Namenbilder, which feature the names of West’s friends in relief on brightly coloured panels, make you think of children’s art. Replace “Franz” with “Daddy”, and you can imagine a young girl painting one of these in a nursery.

Childhood is an important undertone in the Passstücke. These are sculptures which, like toys, you can handle yourself. At least, you could once. West died in 2012, and most of the Passstücke are too delicate for human hands now, so can only be looked at from the other side of a glass box. West would enjoy the irony.

Kollega (1988) is papier-mâché, and looks like a cross between a volcanic rock and an Oceanian head sculpture. The volcanic-paper vibe comes through again and again in the later West, and is made even more intriguing by the enigmatic commentaries which his friends wrote for them. Kollega apparently allows “the comradeship of the visible” to show through. The gormless, papier-mâché heads of Lemurenköpfe (1992) are scathing satire on Europe’s social democrats, who failed to prevent the rise of extremism in the interwar period. Other objects made from similar materials, dotted over the later rooms, look like shrapnel from a papier-mâché bomb. It’s a perfect image for West, scatterbrained but controlled. He takes elements from our equally scatterbrained modern life, like bottles, chairs, tinfoil, even ideas themselves, and reworks them into parodies of themselves, or things to be marvelled at, rather than used and thrown away. West himself said that he wanted to keep the bottles of the alcohol he drank and incorporate them into his work, because it reminded him that he was the new “shell” for that alcohol, part of the act of consumption.

A centrepiece of the exhibition is Redundanz (1986). It looks like a display room, or a room in a studio, open on one side and dotted with strange furniture: rough iron bent into chairs, sculptures instead of sofas, and a portrait of the artist hung sneakily up high. For West, works like these were about combining different elements into a single artwork, but they also feel like an elaborate parody of fake presentations of reality, as in a shop or on a screen. A real living room makes up one of the closing features of the exhibition, and is actually a compilation of several of West’s works with others’ works weaved in. Here you can sit on a sofa and watch a (very strange and purple) film, considering how West wanted to unite art and life. Part of the strangeness is surely because it’s taking place in the Tate, but this living room suggests that West had life approach art, not the other way around. In the same spirit, he made a giant, worm-shaped inflatable, photographed in a holiday resort and based on one of his wormy Passstücke.

“Fun” is the right word for this exhibition, and not just because Divento came here from the Renaissance. It’s definitely modern art, but whatever your gripes with that movement, you should give West a chance. He never takes himself too seriously, and this actually frees him up to ask serious questions about modernity, media, politics, and art itself.

- Monday:

-

10:00 - 18:00

- Tuesday:

-

10:00 - 18:00

- Wednesday:

-

10:00 - 18:00

- Thursday:

-

10:00 - 18:00

- Friday:

-

10:00 - 22:00

- Saturday:

-

10:00 - 22:00

- Sunday:

-

10:00 - 18:00